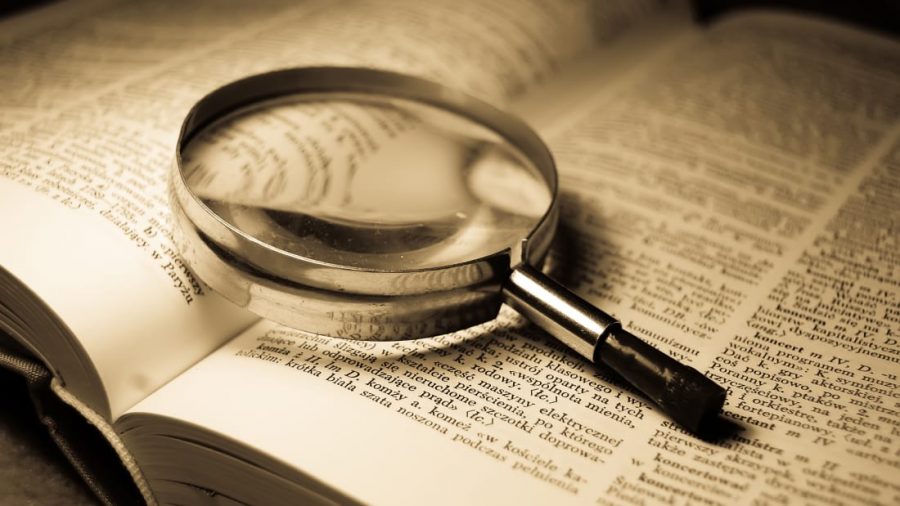

And Then There Was the Word

A Column About Our Language

Many years ago I wrote over 90 columns about our language for the Simmons Voice. Then I took a break. It’s time to start up again. Maybe I can make it to 100. Let’s start with something contemporary: quid pro quo.

Many commentators have remarked about this Latin (now English) phrase, so let me add my voice.

To begin, while the phrase comes directly from Latin, its use by English speakers over many decades has brought it into our language, so I guess the italics I used above should be removed. It should be printed in (ironically) roman type.

The words translate simply as “something for something.” And in its original meaning, there was no sense of anything nefarious or illegal about it. I give you a book and you give me something in exchange: a pot, a plant, or even cash. But in the present political climate, and with the possibility of someone’s having done something ethically or legally iffy, the phrase has taken on a suggestion that one party is doing something suspicious, something that he or she could be censured for. Or worse than censure, if the act was outright illegal. This meaning emanates from the circumstances in which the phrase is used. It doesn’t have to be taken that way, but because of its long-standing use as an attack strategy, it has come to mean that one party is holding the reins, the other is left holding the bag. Or that one party is pulling a fast one on another, who must comply with the other’s wishes or demands before getting what is rightfully his in the first place. The “something for something” situation is no longer innocent; it is complicated and fraught with the possibility of serious consequences.

Sometimes the situation dictates how a word or phrase is to be taken, even if that interpretation is wrong. When I was an undergrad at Berkeley, the Free Speech Movement was on (I just dated myself!), and students were bent on shutting down the campus to get across to the administration that students’ rights had been trampled on. The grinding to a halt of all campus operations was called a moratorium—literally, a pause, a delay of action. The classes were going to be stopped; so was the normal operation of the campus. There was going to be a moratorium of normal activities.

Word got around that there was going to be an impromptu lecture at the Greek Theater on campus—a talk about the moratorium. One person said, “We’re going to hear about the moratorium at the Greek Theater.” Then I heard people saying, “Are you going to the moratorium?” As if it was a place to go to. And for about a week I heard hordes of students saying, “I went to the moratorium.” The circumstances led to the misuse of the word, based on people’s ignorance of what the word actually meant.

Likewise, the circumstances of “quid pro quo” have led people to assume that it means doing something that could be illegal, when the simple words themselves do not impart that meaning. (Though by now that meaning is pretty well established.)

What was fascinating to see with moratorium was that a word that was almost never spoken by anyone before the Free Speech Movement event was suddenly on the lips of thousands—students, faculty, administrators, groundskeepers, custodians (who had to clean up the Greek Theater after the event), and the general public who came along for the spectacle. And, of course, the reporters who covered the event—students from the Daily Cal (where I was a reporter) and writers for the San Francisco Chronicle. Like skinny ties and bell-bottom jeans, the word came into vogue for a brief moment, and by the resumption of classes a few weeks later, moratoria (or moratoriums—both plurals are acceptable) were only a memory. The word was relegated to its proper place in the dictionary, and, most of the students and many others probably never used that word again, except possibly to recall the thrill of the Free Speech Movement.

With “quid pro quo,” however, the event is not localized as the Berkeley word was. It is national—probably even international, since we now have Twitter and Facebook and many other social media, and we now have satellites beaming our lunatic politics all over the world. And with this contentious political climate—with the quid pro quo at the center of the contentiousness—the phrase is destined to become more widespread than moratorium has become.

But it is not in our normal word hoard—that is, it is a phrase that we probably never uttered before the Ukraine business reared up. And most people don’t want to sound like snobs, since we want to fit into our social groups comfortably and unostentatiously. So people are likely to let the phrase go when the whole presidential business blows away. We are almost certain to see a moratorium on the use of “quid pro quo.” And it can’t be soon enough. I am quid pro quoed to distraction.