Although there have been many recent attempts to “diversify” the field of technology, virtually all of these efforts end in failure–or, more commonly, mediocrity. Diversity in technology is not increasing by any significant means, nor does it seem poised to do so in the near future.

Currently, white men comprise the overwhelming majority of technology ventures, including startups; tech giants such as Google, Facebook, and Microsoft; and companies which may not have a specific tech focus but still have large IT or tech development departments. The phrase “diversity in technology,” and iterations of the same, have come to be an empty, meaningless phrase that essentially means “anyone in technology who is not the majority.”

From a gender standpoint, even social media companies such as Pinterest and Instagram, whose users primarily self-identify as female, have development teams of mostly men. Although approximately 80 percent of Pinterest users are female, women account for just under 30 percent of the company’s engineers.

These divides aren’t just bad statistically, they indicate another underlying problem: the primary users don’t have much say in the final product, which creates a divide between the developers and users.

Although there have been many steps taken recently by companies, educators, and nonprofit organizations alike, curing the diversity problem in technology isn’t as easy as “add women and stir.”

For one thing, even though there are a lot of initiatives to increase young women’s participation in tech as early as elementary, middle, or high school, programs actively encouraging diversity dwindle as students travel further on in their educational careers. In college computer science programs, women are hugely outnumbered and face bias from professors, department chairs, and peers.

Another big issue is that in spite of diversity measures in companies’ hiring practices, these diversity goals are seen as just that: goals. There are no quotas in place, no hard-and-fast numbers, because if recruiters hire “too many” women, there are complaints that they aren’t as talented and were hired “just for the numbers.”

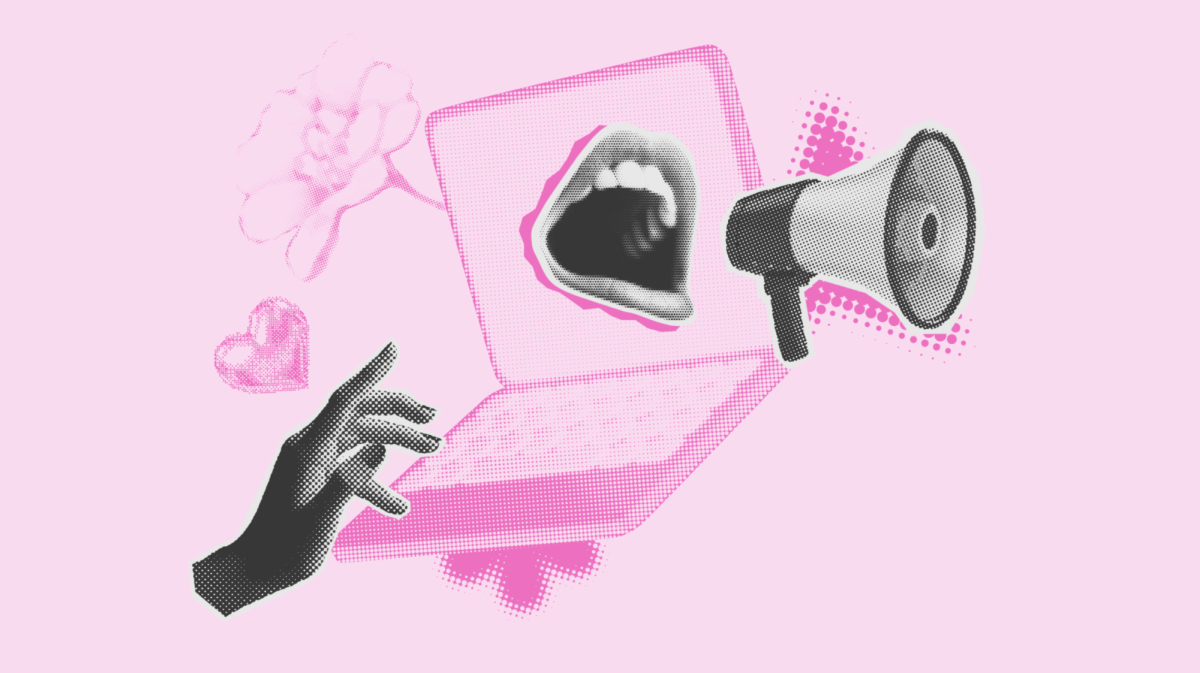

And even if women manage to overcome the first of many hurdles and are hired into a tech job, new employees face a whole slew of issues at companies, including deeply ingrained sexism, the expectation that women new to the workforce will fill a maternal role, or that the “girls” don’t fit into “company culture.”

“Company culture” is, in reality, a form of gatekeeping that serves to keep highly qualified female tech workers out of technological ventures. Generally, this just boils down to the fact that women fail to fit easily into the general “fraternity” attitude of many startups.

These phenomena lead to women existing as token employees, often held up as shining paragons of a company’s “diversity,” even as women continue to comprise under 20 percent of employees in most tech companies.

Earlier this year, the Apple Worldwide Developer Conference (WWDC) featured two women during the keynote, Jennifer Bailey and Susan Prescott, and the conference was hailed as one of the most diverse in years. While Bailey and Prescott are indeed accomplished in their respective fields, and they undoubtedly deserved to be included among the list of speakers, a conference with two women out of a total of four keynote speakers should hardly be heralded as “diverse.”

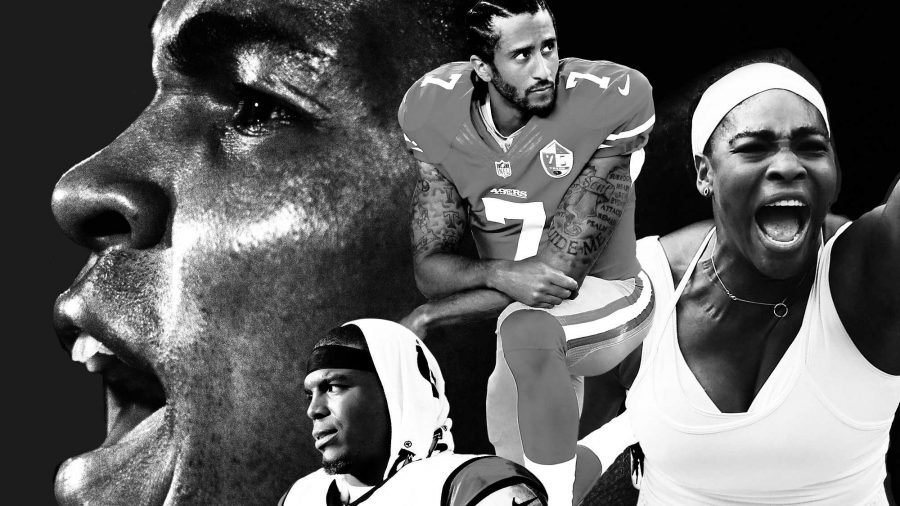

To compound the issue, the majority of women in tech are white, which provides a hugely limited view of feminist activism in technology. Racial diversity in tech is abysmal across the board regardless of gender. Women are already hugely underrepresented in the field, and as a result, minority women often become token “diverse” employees and face constant workplace discrimination.

It is incredibly important not to conflate gender and ethnic diversity in technology as one and the same, which is a common pitfall.

Although there are multiple facets that must be taken into consideration when working towards improving diversity in technology, some of the most crucial are developing support systems for new tech workers who aren’t the “average tech worker,” (read: white men) both before and during employment; educating people who are well-established in computer science fields about diversity issues and how improving diversity ultimately improves technological pursuits; and holding schools and employers to higher standards with regard to respect for their students and workers.