By Shen Gao

Staff Writer

Every day each of us breathes in and out, and when we exhale, we disperse bacteria into our surrounding environment from our own microbiome inside our body. It is believed that we emit up to 10 million biological particles per hour, and this phenomenon undoubtedly contributes to the spread of pathogens to other people and onto surrounding surfaces.

Researchers from the University of Oregon reached a breakthrough conclusion from a recent experiment. In a peer-reviewed article published on PeerJ, it has been demonstrated that individuals emit a unique microbial cloud when breathing.

Streptococcus, propionibacteria, and corynebacteria are some examples of bacteria that can be found on the human body. Non-harmful species of streptococcus often reside in the mouth, skin, intestine, and upper respiratory tract of the human body. Propionibacteria and corynebacteria can often be found as part of the skin flora, which include all microorganisms living on the human skin. The researchers found that different combinations of these bacteria and other bacteria are key to identifying individual people by their own microbial cloud.

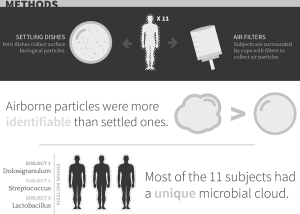

A total of 11 participants were included in the two studies conducted. They were healthy individuals who had not recently taken antibiotics. They sat in sterile, sanitized experimental chambers, and were surrounded by bacteria filters that caught the particles being breathed out.

The first experiment included 240- and 120-minute sampling periods of a single occupant sitting in the experiment chamber. The second experiment included having each occupant sit for two 90-minute intervals.

The analyses that followed the experiment focused on identifying and classifying whole microbial communities rather than identifying singular pathogens. Using rRNA sequencing, the researchers were able to characterize the bacterial contribution of a single person in the study.

To provide a control group, the researchers sampled and analyzed air in an identical experimental chamber that was not occupied by humans, as well as air from exhaust air sources. In addition, the researchers measured and analyzed microbial communities in settled particles surrounding the individual in order to see if there were differences from that of a microbial cloud emitted by a participant.

In under four hours, most participants were clearly detected by their bacterial emissions in addition to their personal contribution in settled particles on surrounding surfaces. In addition, the identification of some individuals could be achieved. The researchers concluded that each of us emits a unique microbial cloud, and that the contents of the air occupied by a person is different from that of an area unoccupied.

Although it is still uncertain if individual persons can be identified among a crowd, this application certainly can be developed in order to contribute to the study of contagious diseases and the field of forensic science.