By Roxanne Lee

Staff Writer

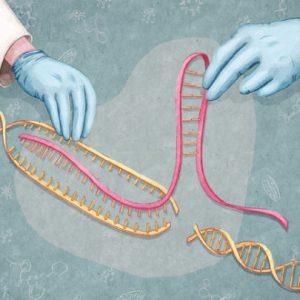

The National Academy of Science and National Academy of Medicine released a report this past Wednesday on how scientists should go forward with human genome editing, entitled “Human Germline Editing: Science, Ethics, and Governance.”

The report by the expert committee focused on germline editing, or heritable DNA alterations. A press release from February 14 said that clinical trials editing the human germline could be allowed in the future, but only to correct disease and disability, and not to enhance health or abilities. Such edits would include adding, removing, and replacing DNA base pairs in gametes and early embryos. Somatic therapy, non-inheritable genome editing, has also had the same precautions as germline editing, and should be used to treat diseases such as cancers, and not for enhancement. The committee stressed that the guidelines should apply to endeavors around the world.

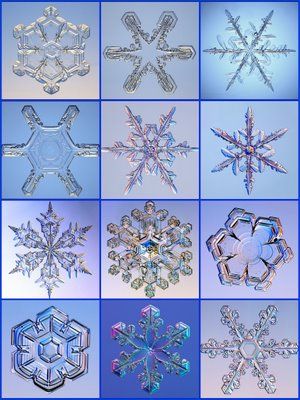

The decision goes against the one made by an international group of scientists in December 2015, which said that gene editing with CRISPR, which stands for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats, should not result in pregnancies.

The report has been put together in part because of the recent uses of CRISPR. Gene editing is not new, but the use of the new gene-editing tool has led to a huge expansion of gene editing possibilities. CRISPR is a technology that lets geneticists and medical researchers to edit a genome by altering or adding pieces of DNA. It is faster, cheaper, and more accurate than previous gene editing tools.

Alto Charo, a biochemist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison law school who co-chaired the panel, likened the decision to something like a yellow light rather than a green light for the use of CRISPR on humans. The ideal goal is to use it where it’s needed, like preventing people from being born with debilitating inheritable illnesses. As the committee said, “Caution is needed but being cautious does not mean prohibition.” The Committee laid out a list of conditions that would need to be met before clinical trials with genome editing could commence.

The list includes rules such as the restriction of the technology to prevent a serious disease or condition, and that credible preclinical data on potential health benefits of performing genome editing must exist before the experiment takes place.

For the most part, CRISPR is not ready for use in humans, but the committee is setting rules and codes for when human trials can be carried out, which could be fairly quickly with the development of CRISPR. Reports by the committee hold no legislative power, and any final decisions will need to be made by local and federal governments around the world. However, they still influence policy decisions around the world when it comes to research.