By Adeline McGrath-Sheehan

Contributing Writer

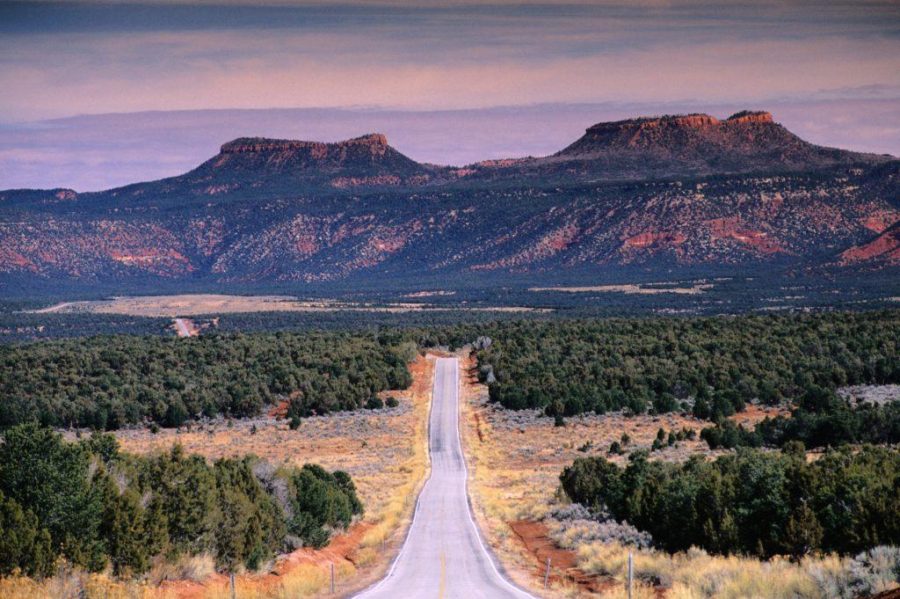

Jumbo Glacier is a mountain in the Regional District of East Kootenay in southeast British Columbia, Canada. It is 1,700 meters in elevation and one of the most coveted places to ski in North America.

So coveted, in fact, that for almost a quarter of a century, the Ktunaxa Nation, conservationists, backcountry skiers, and many more have fought against its transformation into a ski resort. They don’t want to allow this beautiful ski area, the local wildlife, and the sacred ground of the Ktunexa First Nation to be destroyed by the commercialization the transformation to a ski resort may allow.

Vancouver-based architect Oberto Oberti first submitted the proposal for the Jumbo Glacier Project in 1991. The ski area would include 369 hotel rooms, 240 townhouses, 970 condo units, 143 chalets, 22 lifts with gondolas, and various restaurants and retail stores in between. The argument for the creation of the proposed large-scale ski resort is that North America does not have any skiing conditions like Jumbo. Supporters believe that the resort would spur the growth of the tourism industry in British Columbia and create jobs. This is true; some 800 jobs would be made just in the upkeep of the resort alone, not to mention the years worth of hired construction workers. It is possible that the project would impact the economy of British Columbia and keep generations of families in the community employed, reducing the need for locals to leave to find jobs. However, locals don’t seem to agree.

In 2004, the locals marched in the streets of Nelson, BC to protest and to raise awareness for the issue that has affected them continuously throughout the past 25 years. They remain adamant that with the amount of ski resorts nearby being in the double digits, the addition of one in this particular valley is unnecessary, and would additionally bring income away from those establishments.

“Where is the need to pave over more wildlife in this world?” Nick Waggoner, director of the 2015 documentary “Jumbo Wild,” asks. Oberti, however, continues with plans to go around the environmental review process, which would stop his development due to not meeting all 195 of the requirements for environmental approval by the government. Now supporters of the Keep Jumbo Wild movement are asking: what needs to be done to end this 25-year-old battle and protect Jumbo for good?

The documentary “Jumbo Wild” can be found on Netflix and Vimeo, and there is an ever growing petition that says “NO to development in the Jumbo Valley, and YES to permanent protection” that can be found online.