By Roxanne Lee

Staff Writer

In September of last year, a woman in the U.S. died from an antibiotic-resistant infection, a worrying sign of things to come.

The woman, whose name is not available, was in her 70s and was originally from Washoe County, Nevada. She had recently returned to Nevada after a stay in India, where she had been repeatedly hospitalized for an infection that had set in the bone of her leg and hip after she broke her leg.

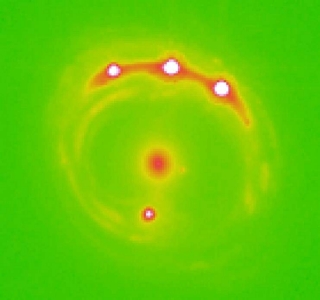

She was hospitalized in a Nevada hospital in mid-August, where it was discovered that she had Klebsiella pneumonia, a kind of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE). CRE are gram-negative bacteria that are very difficult to treat as they are resistant to many forms of antibiotics.

The hospital tried all 14 kinds of antibiotic they had on hand to treat the infection but nothing worked. The woman died of septic shock in September. Later testing showed that none of the 26 kinds of antibiotics available in the U.S. would have been able to stop the infection. It might have been treated by a drug called Fosfomycin, which is not licensed for use in the U.S., but is licensed for use in Europe.

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria are a serious issue that is getting worse. According to a 2013 CDC report, 2 million people are infected with antibiotic-resistant bacteria every year, and 23,000 die as a result. It usually infects patients in hospitals, nursing homes, and other healthcare settings, and patients on long courses of antibiotics or who require equipment such as catheters and ventilators are even more at risk. But where are these bacteria coming from?

Bacterial strains gain antibiotic resistance through both the over-prescription of antibiotics and the misuse of antibiotics, such as not finishing a prescribed dosage of them. Antibiotics kill sensitive bacteria, but leave the surviving ones to grow and multiply in the space left behind. The woman in Nevada who died mostly likely caught the antibiotic-resistant bacteria from her stays at hospitals in India. Antibiotic resistance rates are quickly climbing in India, where increasing wealth is allowing more people to demand antibiotics for illnesses that don’t require them, like minor infections such as colds.

The increased exposure allows bacterial resistance to antibiotics to increase much faster. In 2015, a surge in Klebsiella pneumonia, the same bacteria that killed the woman in Nevada, was recorded in the country. Similar surges are being observed in countries going through similar economic changes as India, such as Vietnam and Kenya. To complicate matters, we don’t know how many antibiotic resistant infections there are right now. People can host such bacteria and not suffer any negative effects, and then pass them on to other without knowing about it. Dr. James Johnson, a professor of infectious disease studies at the University of Minnesota, says that this is a sign of worse things to come in the future. He says that when people ask him, “How close are we to the edge of the cliff?” he replies with, “We’re already falling off the cliff.”

There are possible solutions to help slow the problem, if not outright stop it. One solution that would help would be using less antibiotics in farming, as 2/3 of all antibiotic usage comes from the farming sector, in particular phasing out the practice of putting antibiotics in livestock feed.

Stopping the prescription of antibiotics for conditions they don’t treat, like viruses, is also necessary, as well as increased focus on finding out what country patients may have been in before being hospitalized in the U.S., as geographic information can give doctors a better chance of finding out what kind of infection the patient may have.

It is too late to stop the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, but if the necessary changes are made soon, it may be possible to slow their progression, and thus protect those who are most vulnerable to infection.