By Kaydee Donohoo

Staff Writer

We often picture the universe as galaxies upon galaxies stretching beyond a size we can even conceptualize.

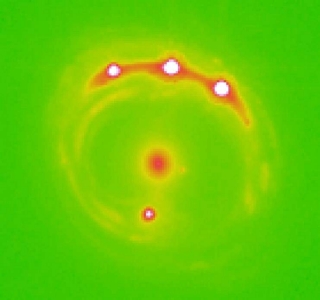

However, increasingly powerful technology allows us to locate better visualize distant celestial bodies, even those outside the reaches of our Milky Way. Recently, the University of Oklahoma discovered a cluster of planets 3.8 billion light-years away. Astrophysicist and professor Xinyu Dai, with postdoctoral researcher Eduardo Guerras, found the planets with data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, a space telescope controlled by the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory.

“Until this study, there has been no evidence of planets in other galaxies,” the press release from the University of Oklahoma states. The smallest is the size of our moon, with the largest being as big as Jupiter.

“We are very excited about this discovery,” says Dai. “This is the first time anyone has discovered planets outside our galaxy. These small planets are the best candidate for the signature we observed in this study using the microlensing technique. We analyzed the high frequency of the signature by modeling the data to determine the mass.”

As the Washington Post explains telescopes cannot visualize anything at such a distance, therefore Dai and Guerras used Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity to make the discovery. The theory describes how light bends when pulled by gravity. The light to aid this discovery came from a distant quasar, the nucleus of a galaxy with a swirling black hole that gives off strong radiation. The newly discovered planets are between the quasar and NASA’s telescope, and therefore the gravity of this distant galaxy bends the light that heads towards our galaxy. This effect is called microlensing.

Microlensing first identified planets outside our solar system but still within the Milky Way, and is so far the only known way to observe any celestial bodies in such far reaches of space.

“There is not the slightest chance of observing these planets directly, not even with the best telescope one can imagine in a science fiction scenario,” said Guerras. “However, we are able to study them, unveil their presence and even have an idea of their masses. This is very cool science.”

“Probing Planets in Extragalactic Galaxies Using Quasar Microlensing,” a paper on the study by Dai and Guerras has been published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.