By Olivia Hart

Staff Writer

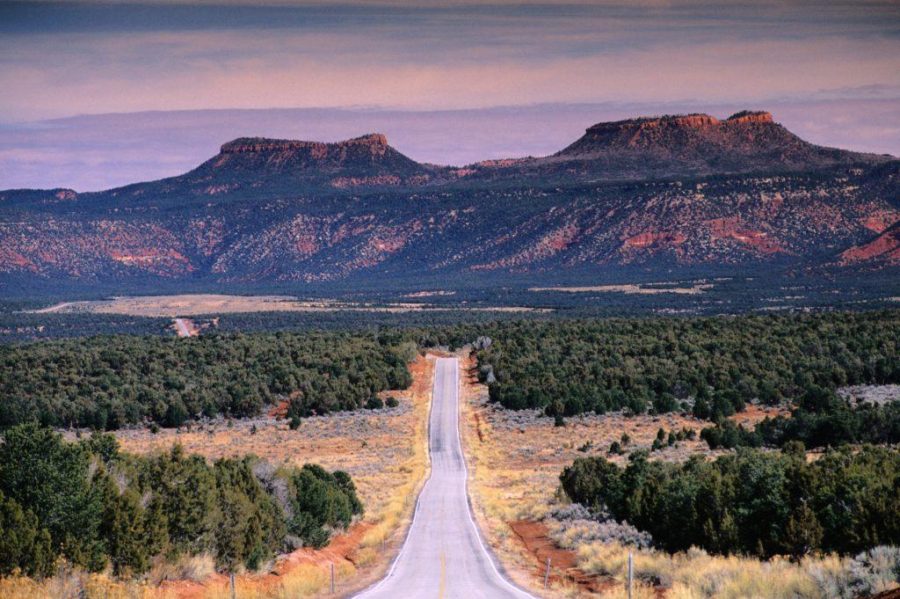

An unusual volcanic hotspot in New England has called into question traditional knowledge about volcanic activity.

“It challenges the textbook concepts taught in introductory geology classes,” said Rutgers University professor Vadim Levin, who coauthored a study of the hotspot. Hotspots occur when a tectonic plate shifts over a hotter part of the Earth’s mantle, causing a bubble of molten lava to rise up from the earth’s upper mantle (asthenosphere). This particular hotspot, named the Northern Appalachian Anomaly (NAA), spans 250 miles underneath Vermont, Massachusetts, and southern New Hampshire. This signals potential future volcanoes in the typically dormant region.

Since the 1970s, scientists have been aware of the heightened temperature and seismic activity of the NAA, but past data did not fully express its strength. Originally, it was believed to be a remnant of a much older regional hotspot that existed one hundred million years ago. However, using recently collected data, the researchers found that the development is much newer—tens of millions of years old—and is about twice as hot as previously thought. If the hotspot continues to grow, it could burst through the crust in a volcanic eruption – the first on the east coast since at least 50 million years ago.

Most volcanoes and similar phenomena take place at plate boundaries (where tectonic plates meet), but New England is not located near a plate boundary. For that reason, the area has been referred to as a “passive margin,” where little volcanic action occurs. However, the NAA may change that perception.

“We did not expect to find abrupt changes in physical properties beneath this region, and the likely explanation points to a much more dynamic regime underneath this old, geologically quiet area,” said Levin.

Despite the shock surrounding the recent findings, current residents of New England have nothing to worry about. The NAA is developing slowly, and has not reached close enough to the surface of the Earth’s crust to affect life above.

“Maybe it is too small and will never make it,” said Levin. “Come back in 50 million years, and we’ll see what happens.”

Levin worked with a team from Rutgers and Yale University on the study, which was published in the journal “Geology.” The team used data from the National Science Foundation’s EarthScope project, which employs geophysical measurement tools to learn about the North American continent’s seismic activity and evolution.