By Taylor Rapalyea

Staff Writer

“You didn’t mention he was black.”

My colleague expressed her surprise when I mentioned that one of my friends is in fact, not white. We had been discussing a recent study conducted by Media Matters that found white men represent a huge majority of guests on Sunday morning talk shows, a majority disproportionate to their demographic.

Her argument had been that perhaps it was because black people were more likely to use slang, and as offensive a statement as it was, I calmly brought up my friend, a journalist I admire.

I had never mentioned that he was white, either.

It had been years since I heard that assertion, that I should “warn” someone if a person in my life is black.

I can never pretend to know the level of racial microaggressions that occur daily. As a white woman, I am not the brunt of them. I fully admit I have that privilege. But I witness these small attacks often.

I hear conversations that begin with, “This is going to sound racist but…” and see people making assumptions about entire races constantly. Even at Simmons, an institution generally considered to be a liberal campus.

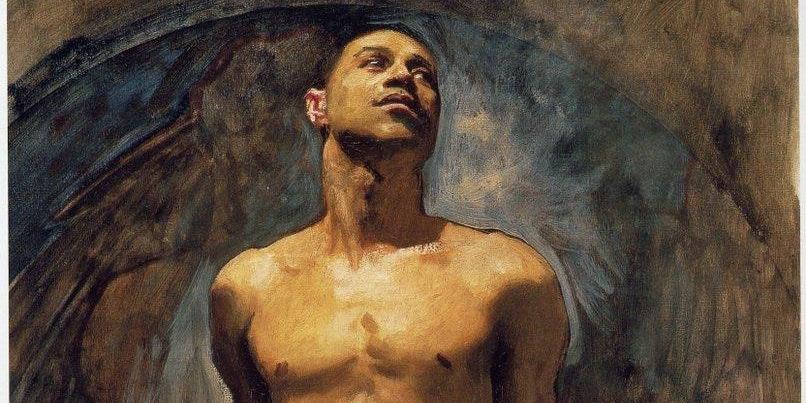

Racial microaggressions are defined by Psychology Today as acts of subtle bias. The typical example is when someone clutches their bag or briefcase closer when passing by a black individual. These actions convey clear messages that undermine minorities. In this case, the suggestion is that black people are more prone to crime.

The Atlantic recently published an article based on the idea that Black History Month isn’t improving the lives of black individuals. The month champions legends – untouchable examples of heroic figures – but doesn’t address “everyday interracial encounters.”

Shauna Deleon is a Communications major at Simmons. She often feels as though she’s being paranoid or oversensitive when she experiences these microaggressions, even though it’s a very real trend.

“Sometimes I can’t even blame them because they don’t know what they’re doing,” she explained. “I swear this morning this guy was mad that he had to sit next to me because I’m black.”

She described the man as sitting forward in his seat while leaning away, tense and uncomfortable.

“I hate calling people out because I know I’ve probably made troubling comments based on race, and I have a deep fear of being a hypocrite,” Deleon said, almost apologetically. Asked who typically makes her uncomfortable with racial microaggressions, she laughed. “It’s just people that I’ve met since I first came to Simmons. I thought they knew me enough and knew what annoyed me enough to know not to do these things.”

It matters. Black individuals sometimes feel that they have to shrink themselves so as to not come off as threatening to other races, as noted by the Atlantic article. If they don’t, it can occasionally result in arrest, or even death. Seem extreme? Michael Dunn of Florida fatally shot a black teenager in November for allegedly playing his music too loudly, and it wasn’t exactly an isolated incident.

We need to educate ourselves on the phenomenon of racially-based microaggressions. We may not think of ourselves as racist, but you don’t have to be blatantly biased to engage in these types of interactions. And equally important is to call others out on their subtle prejudices, even though it can be hard.

And if someone else calls you out, feel free to make your case. But try listening, too, instead of listing off excuses.

Next time a black individual passes you by, consider whether you would react the same way to a white person, and take note of whether you’re clutching your bag closer.