By Kallie Gregg

Staff Writer

Over the course of three acts in the Boston Ballet, dances move from traditional ballet into innovative, contemporary dance, without ever losing their aura of captivation.

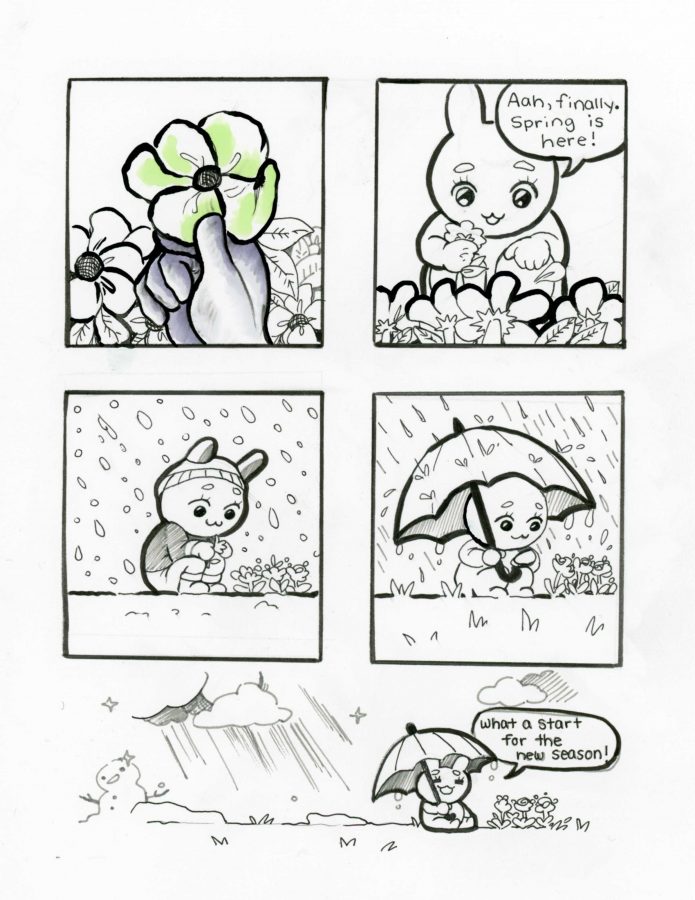

The first work, George Balanchine’s “Donizetti Variations,” was the most balletic of the evening. The “Donizetti Variations” evoke the coming of spring with pastel pink and blue costumes and the playfulness of the dancers. The work consists of a principal couple and an ensemble of three men and six women, all of whom maintain a delightful balance between the light, near-flirtatious air of the piece and the necessary precision and control of movement for their level of dance.

The mood shifts seamlessly from bouncy and at times comedic (in one moment, an ensemble dancer steps forward for an “impromptu” solo and promptly stubs her toe), to a dreamy almost music box-esque sequence in the first pas de deux.

The evening’s titular act, Jirí Kylián’s “Wings of Wax” was a much more somber turn, but equally enthralling in its intensity. Set beneath a massive tree hanging upside-down from the rafters and a single spotlight which orbited it for the duration of the work, “Wings of Wax” manages to communicate a desperate sense of isolation, even with eight performers on the stage.

The dancers move simultaneously together and apart, ensembles and duets based in choreographic harmony which nevertheless telegraph an encompassing loneliness—at one point, the four female dancers move as if trapped in quicksand while one of the men dances frenetically between the, none of them able to transcend whatever barriers hold them apart.

In the finale, “Cacti” the audience departs completely from the ballet of Balanchine and the fraught heartbreak of “Wings of Wax.” Sixteen dancers perch on large, white tiles and move atop them while a string quartet accompany them from the stage. An unseen narrator drawls about the meaning of art, peppering his speech with near-incomprehensible academic jargon.

As the audience lets out helpless peals of laughter, the dancers exit and re-emerge, each bearing a potted cactus. “It is post-modern, and pro-cacti,” the narrator murmurs. Later on, two dancers engage in a faux-rehearsal, where the narrators now grant the audience access to their thoughts. “I always forget this part,” one of them muses. Towards the end of their duet, one of them decides they need a little distance. “But what about the cat?” the other asks. A stuffed cat rapidly descends from the ceiling in a cloud of dust, landing with a distinct thunk.

Through the absurdism and comedic nature at “Cacti’s” core, there is still a beautiful artistry to it—the sequence where the dancers move atop the tiles, in perfect sync with the quartet, is especially striking.

“Cacti” does well to remind the audience that art is more meaningful when it is accessible, not less. The narrator reminds us that even if you are unstudied in the art and criticism of ballet, you can engage with the beauty of the medium and enjoy the innovation and talent on display from the dancers, musicians and, choreographers. The beauty of all three acts is enhanced when keeping that in mind—whether or not you really know what is going on, it is easy to see the show for what it is: a masterwork.