By Lindsey Stokes

Staff Writer

Simmons School of Social Work, in partnership with the Massachusetts Institute of Psychoanalysis Academic Outreach Committee, and Psychology and the Other’s Psychosocial Work Group hosted a cross-disciplinary panel discussion Monday on the effects of race, and racism clinically, and in culture.

Individuals of different ages, races, and educational backgrounds streamed in to the Paresky Center as moderator Dr. Johnie Hamilton-Mason, Simmons professor of social work, began by listing the extensive credentials of panelists M Fakhry Davids, Professor Lisa Lowe, and Dr. Usha Tummala-Narra.

Author and training analyst of the British Psychoanalytical Society, M Fakhry Davids began the discussion by giving a brief outline of his work, including his theory of internalized racism, or issues of race that are external, but eventually come to be internalized.

According to this theory, an us-them structure based in paranoia is formed. This external division eventually gains a new meaning for the individual rooted in personal experience.

Born in apartheid South Africa, Davids’ concept of racial divide was cultivated from a young age: “ If you grew up, as I did, in an apartheid society, you became either one, or the other. I was on the black, or brown side.”

Davids illustrated the case of “Mr. A,” a patient whom he saw regularly at an office in England for over a decade. During one session with Mr. A, Davids reported his patient lashing out, verbally assaulting him.

“I felt racially attacked by my patient,” said Davids “But as a clinician I had a stern talk with myself. I must dismiss this as my own issue, not against my white patient.”

Diving deeper into the issue, Davids discovered after conversing more with Mr. A about this attack that it had stemmed from the psychological native/immigrant divide.

“That relationship between the native, him, and the immigrant, me, created a racial structure that even he, the patient, was not aware of” said Davids.

According to Davids, the racist ideals seen in Mr. A are organized defense systems in the mind that attempt to ward off anxiety. Eventually, instead of discrediting your fantasies about your “racial others,” Davids explains, you come to turn those fantasies into facts, searching for more information that supports your fantasies along the way.

“After one of these difficult sessions I was driving home and I saw the police zoom by me on the highway,” said Davids. “I thought to myself, ‘I bet I wont find a real crime scene with them but some poor black guy stopped.”

With his personal experiences of oppression in South Africa, Davids self-reflected to better understand the complicated relationship between himself and Mr. A.

“I had already worked with the idea of being harassed by the white authority in my country,” said Davids. “I idealized white people. I gave them the status of what it feels like to be black. My internal racism as a black person was different than [my patient]. These are your racial hang-ups, I told myself. They have nothing to do with your patient.”

Lisa Lowe, Tufts University professor of comparative literature and critical studies of race, colonialism, and diaspora, provided some historical background as well as current events to support Davids’ ideas of internalized racism.

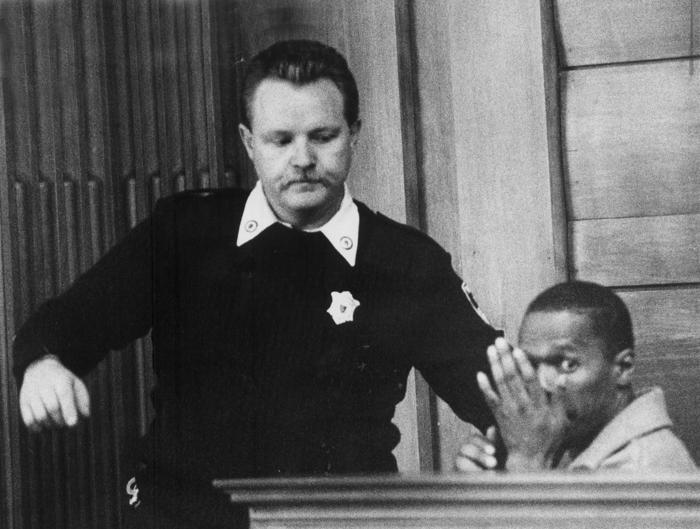

“This summer we witnessed the community outrage and despair at the shooting death of Michael Brown in Fergusson, Missouri,” said Lowe. “The shooting of Michael Brown is not an isolated incident.”

Lowe explained the relation of race and social structure by highlighting the relation between white privilege and black criminalization.

Lowe, however, disagreed with Davids’ use of internalized racism as a way to explain police response in Ferguson, Missouri, or the increased amount of Islamaphobia after the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, and the continued prevalence of this phobia today.

“There is a much longer history of violence as power,” said Lowe.

Dr. Usha Tummala-Narra, Associate professor in the counseling, and developmental education psychology departments at Boston College, concluded the program.

Tummala-Narra used specific case studies and patient testimony to spotlight the effects of racial discrimination on the identities, and life choices of immigrants.

Tummala-Narra described how intergenerational conflicts related to race in immigrant homes, such as stress caused by xenophobia, is left unspoken inside the family, thereby integrating racism into family dynamics.

“Many wonder if events that happened to them were racially discriminant or not,” said Tummala-Narra. “I think that there is a perception of racial minorities that we are always complaining, and that is a very internal feeling. It comes down to whose narrative are we going to believe?”

Tummala-Narra reported that many of the adolescents in a certain case study experienced racial micro-aggressions at school on a daily basis. One adolescent in particular, who was in fact English fluent, was walking down the hall one day when a teacher grabbed her shoulder, yelling, “Hello, hello. Nod if you understand.”

Video testimonial of this student, as well as others with similar experiences, were sent to the school in an effort to start a conversation about race and stereotypes within the district. Despite follow-ups, and repeated inquiries, Tummala-Narra reports the school has yet to respond, even now, six months later.

“This, unfortunately is our social mirror,” said Tummala-Narra. “We all have much work to do.”