By Haley Costen

Staff Writer

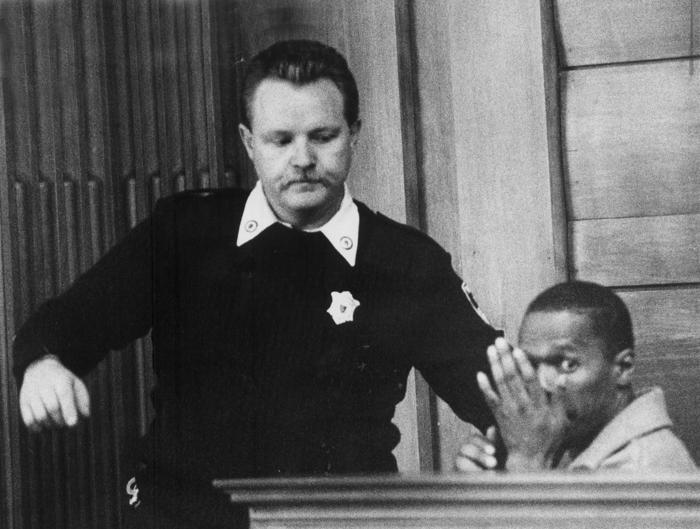

During the apartheid era, the South African police force was notorious for its strict enforcement of laws and brutal methods of controlling the non-white majority. It’s been 20 years since Nelson Mandela became the first black president of the country and South Africa adopted a constitution promising equality before the law and freedom from discrimination, but how much has the police force actually changed?

During the apartheid era, the South African police force was notorious for its strict enforcement of laws and brutal methods of controlling the non-white majority. It’s been 20 years since Nelson Mandela became the first black president of the country and South Africa adopted a constitution promising equality before the law and freedom from discrimination, but how much has the police force actually changed?

Though it altered its name from the South African Police to the South African Police Service (SAPS) in 1994, many citizens feel that the SAPS hasn’t changed much.

“They’re so corrupt,” says Madla Majola. “It’s heartbreaking.”

Majola is the coordinator of the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) branch in Khayelitsha, a sprawling black township outside Cape Town. Although TAC was formed in 1998 to provide education and equal healthcare to all citizens suffering from HIV/AIDS, it now also helps people take action when other problems arise in the community, such as gender-based violence and medical problems like TB and botched surgeries.

Majola says there is a great amount of police corruption in Khayelitsha, home to more than 300,000 people. Many of them live in shacks while relying on one communal water tap and using chemical toilets.

Somali shop owners are tasked with providing biscuits and tea to officers on a daily basis. They have to bribe police to get help after being robbed if they don’t have citizenship papers, according to Majola.

Majola also charges that rapists pay officers to destroy evidence so that their case will be closed due to lack of evidence and that local drug lords also pay off the SAPS. Part of TAC’s job now is to pursue gender based violence cases and to make sure they go to court without the tampering of any evidence.

A recent investigation by the Khaeyelitsha Commission of Inquiry led to future random drug testing among Khayelitsha police officers, according to Eyewitness News.

However, drugs and corruption are not only a problem in the Khayelistha police force, but also in other townships and communities.

Faeze Isaacs has lived in the Bo-Kaap, an area in Cape Town famous for its brightly colored houses and being home to the apartheid-branded Cape Malay population, since she was born in 1966.

While she maintains that life in the Bo-Kaap is much better today than it was during apartheid, she says that children cannot even go to school because of crimes like robbery and rape.

Another Bo-Kaap citizen who prefers to remain anonymous agrees that police corruption is a huge problem in the area.

“They [the police] like money,” he says with a laugh, adding that officers regularly receive money from drug lords and criminals, and that killers and rapists often go to jail and are released the following day.

Sherine Habib, another Bo-Kaap citizen, who worked with the underground African National Congress against apartheid and now leads tour groups through the area, also feels strongly about the police.

While she says the Trauma Unit has been helpful to her organization, Women Against Gender Based Violence, she feels that a lot must be done to change the police force.

“The city of Cape Town needs to put more money into the police,” she says, adding that the disbursement of government funds is not equal or fair.

“The police don’t get paid a decent salary,” she says. “That’s why they take bribes.”

She also says that despite all the changes and the progressive constitution of South Africa, the structure of post-apartheid society still allows white citizens to get better treatment than black, mixed race (called “colored” by South Africans), and Indian communities.

When Peter Trevani, a former professional golfer, came to South Africa to play in the Sunshine Tour from 1955 to 1996, he says he experienced the inequality of the police force firsthand.

He was warned to stay away from black areas like Soweto, Alexandria, and Hillsboro because whites were often beaten or killed in the chaos that followed the formal end of apartheid due to remaining tension from the black majority. However, he says he was treated significantly better by the police due to his race and status.

“The police—who were mainly black officers, would tell us where not to go, and would even offer us rides to places where we would be safe,” he said in an email interview. “One officer told me that police would never go into townships without backup and if a crime occurred at night, they would wait until the next morning to respond.”

Trevani also witnessed tension between black officers and citizens. His caddy, a man living in a black community outside of Johannesburg, saw his own friends in the community attain positions of power as police officers and later use their power against him and his family.

Danny Titus, a part-time commissioner at the South Africa Human Rights Commission (SAHRC), says that police are finding it difficult to work within the standards of human rights, adding that torture is a common practice by the police and that officers sometimes go beyond their power and kill people.

“I could bring you into any police station and there will be torture,” he says with emphasis.

Titus believes that the reason for this behavior is that the police feel misunderstood and apathetic because they feel that the life of a police officer means very little. They’re often the “bad guys.” He also attributes corruption to a kind of arrogance that allows officers to believe they can do whatever they want to someone.

Trevani witnessed this as well, recalling a moment at a country club outside of Johannesburg.

“There was a fenced in area where the black caddies had to stay and if one of the players needed a caddy he could pick one of the black caddies out of the cage. However, the caddies are not allowed to solicit for work; they just have to be lucky enough to get chosen,” he says. “The day I was there, one of the US player’s caddy did not show up at the course and he needed a caddy. One of the black caddies in the cage solicited the player and was instantly slammed in the back with a billy club and then beat up by a black officer.”

“The inequality in this country is immense. You can see the ease in which corruption flourishes,” Titus says.

Chad Wesen, a foreign service officer to the United States Embassy, says that the SAPS are not only corrupt, but also function inadequately.

“I’ve heard that the South African police are functionally illiterate in English,” he says. “If you can’t understand the law, how can you implement it?”

Wesen doesn’t believe that the police force has the investigative capacity to break organized crime or to lead complicated investigations. The police often bungle wire taps and neglect to get search warrants, he says.

Wesen adds that a recent investigation led to the discovery that thousands of police officers had prior criminal records.

According to the Guardian, 1,448 officers with records of crimes like rape and murder were still employed by the police last year, some in high-ranking positions. This number excludes another 8,000 with previous criminal records who were fired or found to have committed petty crimes.

Though the SAHRC is aware of the police corruption in South Africa, Titus says it has decided not to fight the police, but instead to engage with them.

“We must sit with them at the table, look them in the eye, and turn the ship of torture around,” he says, adding that the SAPS have been willing to cooperate thus far.

With more organizations and commissions setting their eyes on the police and with frequent investigations, many hope that the people of South Africa will some-day be able to put their trust in the police force. But that day is still to come.

As a part of the Human Rights in South Africa course, 11 students learned about the history of apartheid and the current social situation of South Africa. In May, they visited the country and witnessed the situation first-hand, speaking with people from activists and average citizens to U.S. diplomats and commissioners. You can check out their blog at http://bit.ly/1rVeGkQ.