By Christine Gronberg

Staff Writer

On his second cup of coffee, Mike Zuma, our tour guide for the day, is speaking a mile a minute as he leads us around his hometown of Langa, the oldest township still standing in Cape Town. He tells our group about the new coffee shop in the visitors’ center as we walk in. It is sparse with white walls and a few tables, and a chalkboard menu listing the coffees and lattes they offer. The pride in his voice is obvious – Langa’s first café is a hit.

The next building Zuma takes us to resembles a classroom, with a square table in the center, surrounded by posters on the walls and dioramas on the floor directly below—architectural blueprints and models for a new pavilion to be built in the courtyard. Zuma says there is a design competition funded by the World Design Project; when the plan with the most votes (marked by red circular stickers) is chosen, construction will begin.

Excited hand gestures and funny accents punctuate his speech as he describes the new programs being brought to the township and the change the people are engaged in to better their lives.

The South African government has trouble reaching everyone, and in the meantime, small community organizations do their best to fill in the gaps, he says. Proactive South Africans are taking matters into their own hands.

Outside the city of Johannesburg, in Kliptown, the oldest section of the South-western Townships (Soweto), we meet Thulani Madondo, who works with the Kliptown Youth Program (KYP). This program provides support for the school-aged children and teenagers in the community.

Services available include tutoring and athletic programs to encourage kids to reach their potential, says Madondo, quoting a common Xhosa saying, “the wealth of the poor is education.” KYP has a variety of programs designed to address teenage pregnancy, HIV/AIDS, and domestic violence through education and the arts.

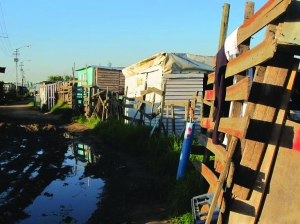

Madondo and his staff encourage the people of this community not only to dream, but to dream big. Most of them live in wood and metal shacks while desperately waiting to receive one of the tiny four-room houses provided by the South African Reconstruction and Development Program (RDP). Madondo argues that those houses cannot fit the large families that need them. Those who now hope to live in RDP housing have stopped dreaming, he says. They should be aiming for a spacious house with a backyard and a pool.

Dreaming is a key part of changing one’s station in life, but hard work is necessary as well, as we learn from Donald Quebeka, whose strength and perseverance become apparent as he tells us about the seven years he spent building himself a new house.

Quebeka grew up in a shack in the black township Gugulethu outside Cape Town. It would cook in the summer and freeze in the winter, he says. Access to housing is promised by the Constitution and so he put his name on the list, but the government failed to keep up with the high demand. There are people who have waited over 10 years for a house and are still waiting, he says.

Instead of sitting back and enduring the harsh conditions of a shack, Quebeka started collecting bricks. He went scavenging at demolition sites and spent his spare time chipping the concrete off them. People thought he was insane, he says, but he kept his eye on the prize—a real house of his own. The year his wife Liziwe delivered twins, Quebeka had one room built, and it became the babies’ room.

He takes pride in the fact that his sons never had to live in a shack, not even for a day: “I didn’t want my sons to taste the same medicine I took.”

While Quebeka built his own house, there are others who already have one but now have to fight to keep it. The Anti-Eviction Campaign (AEC) was founded in 2000, with the purpose of defending those families who are being unfairly evicted. In 1994 Mandela decreed that families would receive ownership of the houses they were in, and it was written into law in the Constitution. This was compensation for the long years of paying rent and being legally prevented from owning property.

Though this law protects some people, there are always loopholes, and new ways are found to exploit those who are vulnerable, as we learn from members of the Western Cape Anti-Eviction Committee. The banks demand the deed to the house as collateral for loans that are continuously passed on from family member to family member until paid in full. The bank can also sell the house without any notice given to the family. Evictions tend to turn violent with the help of police and gangs.

Mncedisi Twalo and his fellow advocates provide families with legal advice and support. Without the AEC representing them, most families have to rely on legal aid from the state, he says. Twalo claims that those cases do not have a chance and do not end well for the victim.

One of the families the AEC is currently assisting is the China family. They are going to court with the AEC behind them.

The AEC does not have a permanent office, but there are always ways of reaching Twalo, either by phone or by word-of-mouth. Twalo, 48 years old, was an activist in the apartheid era, and remains a dedicated servant of the people. Not long ago he was diagnosed with TB. He has been taking medication for six months, but this does not stop him from helping whomever he can. Even when he was bedridden, people would come to him for advice and he was happy to provide it, he says. There are no sick days and no days off.

“I have to be there,” says Twalo.

These are just a few of the many who are devoted to their communities and to helping each other succeed. They are members of small organizations with a high impact on their corners of South Africa.

Their motivation stems from their perception of the government’s indifference. Twalo accuses the government of not only forgetting the poorer classes but also victimizing them. Angry and frustrated, he says, “We are not being protected by the constitution of this country.”

As Quebeka shows us around his impoverished township, his face scrunches with annoyance as he says that things have not gotten any better in Gugulethu in the past 20 years.

In his eyes, the government is struggling to live up to its promises of equality, education and housing. Others point out that the government is only 20 years old, a squalling baby compared to most established states. Though the ANC also has a lot to do, they are not starting a country from scratch. They must undo the legacy of apartheid before they can move on.

Bureaucracy and patronage have slowed progress, and there have been allegations of corruption and mismanagement of funds. President Jacob Zuma has also been accused of extravagant personal spending. In 2013 he made false “security renovations” to his home in Nkandla, including a swimming pool, that were paid for by the government.

Service delivery around the country has been affected by the mismanagement of funds as well as the incompetence of some government officials. One example we heard often was of textbooks that were supposed to be delivered to Limpopo, one of South Africa’s poorest provinces, that didn’t arrive at the schools until the middle of the year.

Zuma argues that the first half of a president’s term is spent collecting data, and that construction and implementation of programs has to wait until the surveys are complete. We saw firsthand that progress is slow when it comes to government actions.

The Gender Commission, mandated by the constitution, is dedicated to monitoring and encouraging gender equality in government and business. When asked how many women actually work within the Gender Commission itself, a nervous chortle escapes the presenter’s lips. He tries to change the grimace on his face to a smile, but it’s too late. The answer—not many women.

He repeats over and over that the organization is not perfect and is trying. It is a start, he says. But many people are demanding more, charging that things are moving at the pace of molasses.

Meanwhile, the social activists push on. As Shireen Habib says, “It’s about love. It’s about heart. It’s about people.”

As a part of the Human Rights in South Africa course, 11 students learned about the history of apartheid and the current social situation of South Africa. In May, they visited the country and witnessed the situation first-hand, speaking with people from activists and average citizens to U.S. diplomats and commissioners. You can check out their blog at http://bit.ly/1rVeGkQ.