Op-Ed: Is there a solution to the child ED boarding crisis?

I got a first-hand look inside the hell that is accessing pediatric mental health care.

October 25, 2022

Content Warning: Suicidal ideation, in-depth description of hospitalization.

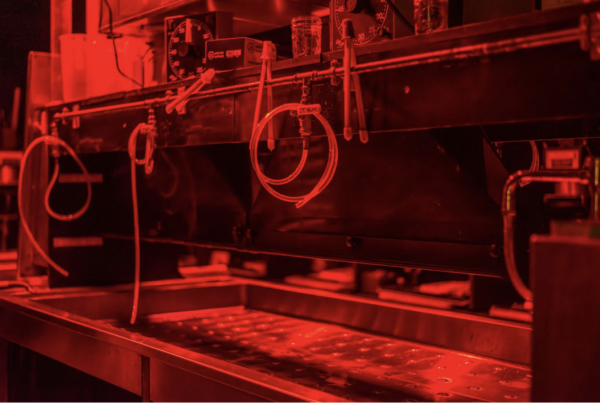

I have been sitting on a cot in the Emergency Room hallway for three hours. One month until my eighteenth birthday, I was in the pediatric wing of my local hospital. My gaze shifted to the surrounding patients in mint green scrubs and grippy socks, matching the ones I was wearing– the bright color signaling that we were psychiatric cases. My mom rested in a chair at the end of my cot and anxiously played Candy Crush on her phone. An older woman sat in a foldable chair next to me, knitting and humming away. She was my one-on-one watchdog, there to ensure I didn’t try to kill myself. An emergency button lay idle next to her. She was supposed to press it if I tried to get out of the cot. Then, I would be restrained by security guards.

Without my phone or a book to entertain me, I resorted to counting. One hundred fifty-seven tiles levitating above my head that I prayed would fall. Twenty-one pediatric patients, eighteen of them in the green psych uniform. Sixteen watchdogs. Twelve nurses running around the hospital wing, primarily concerned with the three non-psychiatric cases. No social workers in sight.

Finally, after sixteen hours, a social worker was available to discuss my case. It was 3 am when she spoke to my mom, then woke me up to talk to me. I was still groggy when she brought me into a separate room to ask why I was in the Emergency Department. I spent the next five minutes telling her about how my mental health had been progressively worsening for the past few months; how I was having five to ten panic attacks every day; how I could no longer look at my schoolwork when I was once a straight-A student; how it took all my strength to turn over in my bed, nevermind leave it; how when I looked around a room all I could see were ways to hurt myself. Do you have a plan to follow through with these thoughts? No. Do you want to die? I think so. Do you think you can keep yourself safe? I don’t know.

After three questions and whatever she heard from my mom, the social worker told me I had two options: go to an outpatient program that would replace school for a few weeks or be an inpatient at a mental hospital.

I spent two and a half days in the Emergency Department before being transported in an ambulance to McLean mental hospital, the best in the world. However, that is not the story of most people who need to be hospitalized for their mental health, and it was not the story of the other patients taking up cots in that Emergency Room. I was one of the lucky ones. The social worker told my mom to use any connections she had because it would be nearly impossible to get me a bed somewhere. Thankfully, through a family friend, my mom was able to get on the phone with hospital administrators. After twenty-four hours of non-stop phone calls, she found me a bed at McLean.

Unlike children as privileged as I, with connections to people on hospital boards, finding access to behavioral health services is a lengthy and tumultuous process. They must rely on ED staff and overloaded social workers to find unavailable beds. Every person I met during my stay at McLean told me about their experience being boarded in an ER. Like me, they received no treatment, just a cot to wait in and protection from killing themselves. However, while I was boarded for only 60 hours, they were boarded for weeks to months.

Emergency Department boarding refers to someone needing psychiatric care but having to wait in an ED because there are no beds available. This delay is worse for pediatric patients than adult ones because of the higher demand for children needing treatment. The issue was escalated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which further overloaded the system. During 2020, the proportion of mental health–related emergency department (ED) visits among adolescents aged 12–17 years increased 31% compared with that during 2019.

This crisis is finally being addressed in Massachusetts with Bill S.107, which should help children access mental health care and lessen the time for ED boarding. The bill requires the secretary of Health and Human Services to create an online portal for data on children currently awaiting behavioral health services. This portal will include why children have waited over 72 hours to be moved from the Emergency Department to a facility to access mental health care and the number of beds available for pediatric patients. The secretary is also mandated to create quarterly and annual reports on the status of children awaiting behavioral health services. Finally, the bill creates a complex case resolution panel to resolve issues surrounding access to services for a child with complex behavioral health needs.

However, finding access to pediatric mental health services will not be solved solely through databases and online portals. The system needs more money allocated to opening mental hospitals to fill the growing demand. It is also in dire need of social workers and mental healthcare workers; the chronic shortage delays providing help to children in need. Bill S. 107 is the first step in addressing the nonfunctioning mental healthcare system, but it cannot be the last. Hopefully, this is just the beginning of a new dedication to adolescent psychiatric care at a time when desperate necessity is progressively growing.

CORRECTION: Oct. 26, 2022

An earlier version of this article included information that did not meet the information handling standards of the Voice and disclosed the private information of a source. That information has been removed from the story.