Hyman Bloom exhibit at the MFA reveals the beauty in demise

October 22, 2019

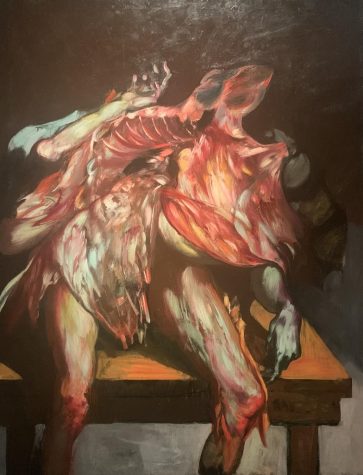

“It’s just so weird,” said the woman behind me as we both gazed at Hyman Bloom’s shockingly graphic Cadaver on Table. A man’s contorted body is shown split in half within the oil painting––his flesh pulled back to expose a colorful array of muscle, tissue and organs. The painting is one of several on display in current MFA exhibit “Hyman Bloom: Matters of Life and Death,” many of which depict similarly uncomfortable images of demise.

Bloom was born in 1913 in Brunoviski, Latvia but moved to Boston with family in 1920 where his painting career took off at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. Figural sketches displayed in the first section of the exhibit highlight Bloom’s fascination with the human body towards the beginning of his career.

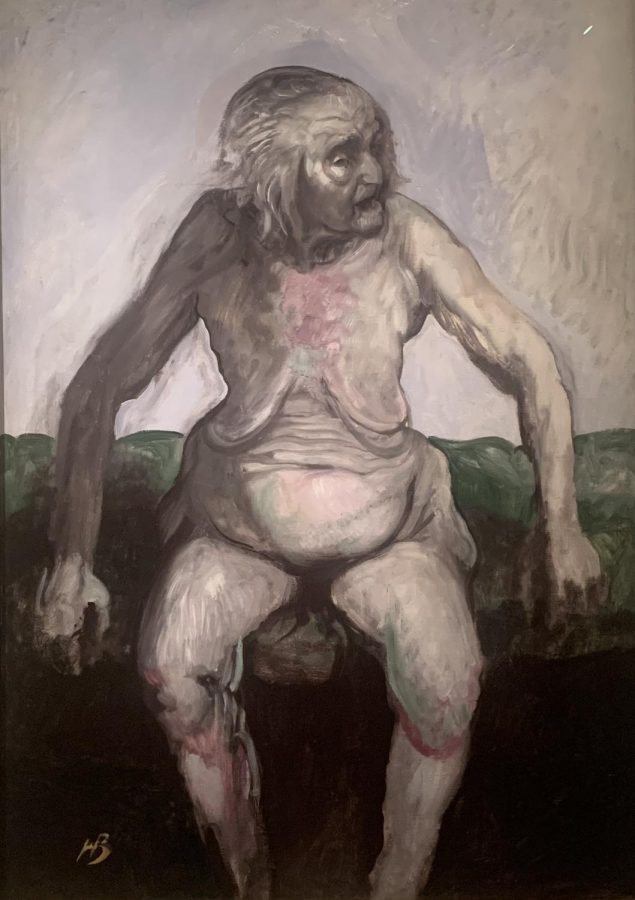

Bloom’s subject interests quickly evolved to those of transformation and decay shown by his many sketches of old women done in colored pencil, crayon, and oil paint. Seated Old Woman in particular features Bloom’s attention to detail around aging: the sagging skin, drooping lines, pale tones, and uneven textures uncover the harsh reality of life’s cycle.

By the 1940s, Bloom had gained both national and global attention for his unique style, appearing in several well known shows including the MFA, but his true big break happened a few years later. In 1943, a visit to the Kenmore Hospital Morgue drastically influenced Bloom to paint what most would consider the stuff of nightmares: dead bodies.

“On the one hand it was harrowing, on the other it was beautiful––iridescent and pearly. It opened up avenues for feelings not yet gelled. It had a liberating effect. I felt something inside that I could express through color,” said Bloom (MFA).

That iridescence is visible in every work of Bloom’s. His gestural brushstrokes seem to give the lifeless a certain vitality not typically associated with still lifes. The inner-workings of chests and spines are continually exposed throughout his paintings, unveiling layers of animated body parts. Even wounds and open sores found in the expired limbs of the deceased, resemble vibrant jewels.

After getting comfortable with the controversial theme of the exhibit, I realized that Bloom’s work redefines how we view dying. Death is arguably humankind’s greatest fear and most harrowing mystery; but by attributing colors and movement to the cold bodies found within morgues, Bloom associated life’s inevitable final stage with a spiritual energy that we needn’t be afraid of.

Bloom’s work further pressed artistic norms when he began observing autopsies in the 1950s. The move from painting static bodies to ones undergoing medical examinations gave Bloom an opportunity to expand his understanding of human anatomy. The autopsies frequently involved more violent and what some would call, “gory,” subject matter that led to criticism. While some artists praised Bloom for his daring interest in taboo art inspiration, many found it too graphic for the public eye––one gallery owner even tried to move some of Bloom’s more explicit paintings from a show to a back room reserved for specifically intrigued visitors only.

Bloom passed away in his New Hampshire home in 2009, but his paintings continue to inspire and intrigue artists and viewers alike. Although his work has endured a wide array of critiques in the past, Bloom’s groundbreaking art is celebrated today. “Matters of Life and Death” will be on display at the MFA until February 23, 2020––I highly recommend paying a visit.