By Sarah Kinney

Staff Writer

She wandered around the Boston Book Fair, weaving in and out the crowd, and had to squeeze a hand between two strangers to pick up a copy of “The Great Science Fiction Stories of 1964” from the New England Science Fiction Association table. Afterwards she spent an hour with her roommate perusing the shelves at Barnes and Nobles in the Prudential Center, flipping through pages, reading backs of books, and caressing spines. Her roommate purchased an anthology of Jules Verne’s work.

In the evening, however, both found themselves not flipping through pages, but swiping across a screen, one on a Kindle and one on a Nook.

“I like my Nook because I can bring it places, like on the bus or on vacation, and then I don’t have to tote around a hardcover book,” said Simmons junior Ashley Hatcher. “But if I had to choose, I’d rather read a physical book.” Despite reports of digital content taking over the printed word, some people are finding balance between them. There is a shift of consumption, but not a takeover.

“I don’t mind reading textbooks on tablets, but when I’m reading for pleasure, I like it to be a hardcover,” said Jessie Kuenzel, a sophomore at Simmons. Mallory Coulombe, a junior at Southern New Hampshire University, prefers hardcover textbooks and paper magazines but looks to electronic media for quickly reading the latest news. Simmons senior Emily Singer reads eBooks for pleasure but says her textbooks are often not available digitally.

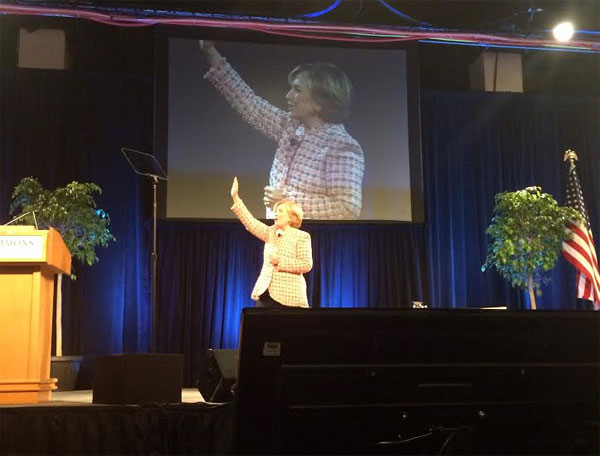

Kyle Newton, author of “Allegiance of a Soldier” and “Lies of a King,” sees the benefit of having both print and digital books. He said eBooks were more profitable though they are cheaper; he can collect 90 percent of the royalties on them, whereas on hard copies he only makes about 25 percent. On the other hand, it is harder to sell the eBooks on a person-to-person basis, like at book talks and signings.

“There’s a lack of connection between the author and his, her readers, which is the most important part of the sale,” said Newton. “In many ways you need to have the two work together: sell at book stores, but promote your eBook like crazy.”

EBooks have been around since the 1990s but became common in the middle of the first decade of the 2000s. The sale of eBooks increased 4,456 percent from 2008 to 2012, but leveled off with a 43 percent growth from 2011 to 2012, according to the Association of American Publishers. In the United States, 23 percent of the population actively reads eBooks, said Jennifer Peterson of the Online Computer Library Center. Currently the largest demographic of eBook consumers are collegeeducated, women, younger than 45 years old, or those who have household incomes over $75,000, according to Random House. “We will see all of this start to change as eBooks become more a part of the reading experience for all Americans, as we see prices start to go down on eBook readers, and tablets themselves,” said Peterson. “They’re already talking about free Kindles.”

A library science graduate student at Simmons said the initial cost of purchasing a tablet or eReader could be a deterrent, which is why she does not read eBooks. EBooks are less expensive than paper; looking at bestsellers, it takes about 20 to 25 book purchases to make up the difference with having to purchase a eReader.

However, with eBooks, there are fewer opportunities to buy used books or resell books. The GSLIS student thought many people bought eBooks for the convenience. Often eReaders allow the reader to purchase on the device, which saves on transportation and storage costs.

Even with the emergence of new technologies, while 81 percent of students believe reading materials will change to digital formats, most people still use a combination of print and electronic media. In 2012, eBooks were only 20 percent of total book sales, according to the Association of American Publishers and the Book Industry Study Group.

“In all the talk about eBooks, we often lose track of the fact that more than three out of four books sold in the U.S. are still printed ones,” said Michael Pietsch, CEO of the Hachette Book Group. Home to some of the largest repositories of printed materials, libraries have been adapting to digital content even before the emergence of eBooks.

“Libraries have always had to supply more than just books,” said Beatley Library circulation desk employee Matthew Miquez, citing that the internet changed many things and that libraries have electronic journals since the ’70s.

“They [libraries] aren’t just a book place, but also a place where people can go to get away and escape in stories,” said Newton. “I think they should have Kindles and Nooks so people can still read and be creative, and maybe even become a place where it is more of a place where people can create ideas, rather than just show what others have done.”

Libraries are working on what Peterson calls the Big Shift Project, so that libraries can offer rental eBooks and devices. Many face restrictions on lending from publishers, which she saw as maybe scaring the libraries from advertising their eBook offerings.

“Even though over 76 percent of you [librarians] all are lending eBooks right now, only about 12 percent of library borrowers have actually borrowed an eBook from you,” said Peterson. “Somewhere upwards of half the numbers change depending on the research you look at but around half of your cardholders do not know you offer eBooks.”

Adam Simard, a junior at the University of Maine Orono, believes paper and electronic books will always exist together. “I think there will always be hard copies of anything artistic or important enough in case the digital one is lost. I also think a large volume of people enjoy holding a book when reading it,” said Simard. “If anything, I would compare it to CDs. The stores that sell them are becoming fewer, but there are still people buying the disks. Besides, there are still record stores, aren’t there?”

“People are never going to completely switch over,” said Simmons junior Krystle Gillietti.