COVID tests, classes and isolation: the story of a first-year living on campus

“I would just make that the center of my day, when I could go to my COVID test, because I actually get to be outside for 15 minutes. I would walk really slowly to get my test, walk really slowly to come back, and just soak up as much of the outside as I could.”

November 17, 2020

It’s a quick procedure. It’s routine for her now, a part of her schedule every Monday and Thursday since August. The short walk from her dorm to the small auditorium in Alumnae Hall is a good opportunity to get outside, away from the four walls that serve as both her classroom and bedroom. Alumnae Hall is quiet. The old linoleum floors combined with the high ceilings would amplify even the smallest noise, if there was any.

Six booths are spread out around the room. Zari Shahgodari checks in at one of the tables set up in the front and makes her way to the testing booth, which is really just a table with a plexiglass divider. A nurse hands her a clear plastic tube and a cotton swab. She sticks the swab into her nose, until the bud of the cotton swab has completely disappeared into her nostril. She skillfully wiggles the swab around to circle her nostril three times. It burns the inside of her nose, but it’s now a familiar sensation.

Shahgodari pops the swab into the tube, hands it back to the nurse, and pushes through the heavy metal doors out into the Boston air. Her COVID-19 test complete, she can now move on with her week. Until, of course, she comes back again on Thursday. This is how it has to be if she wants to live on campus at Simmons University. And Shahgodari is one of only 13 first-years living on campus.

When the university announced on July 14 to keep students home and move to a completely online class model for the Fall semester due to the COVID-19 pandemic, they gave students the opportunity to petition to live on campus. Students could apply to live in the dorms if Simmons is considered their legal residence, if travel restrictions prevented them from going home or if they are employees at local hospitals or other essential agencies. According to an email from the Office of Residence Life, Students could also apply if their other housing options were unreasonable, meaning they do not have a home to return to, their home is unsafe or they are housing or food insecure.

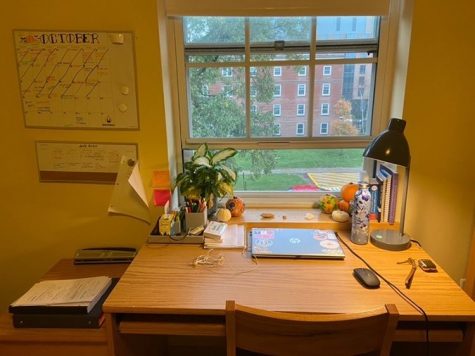

Shahgodari is from the coastal city Port Saint Lucie, Florida, and lives in a one-bedroom apartment with her mother. This small space and lack of privacy caused Shahgodari to worry. She didn’t think she would be able to focus in her apartment. She applied to live on campus a month before the deadline, figuring she’d give it a shot. She moved into Smith Hall in late August.

Coming from Florida, she could only bring two suitcases. Her mom couldn’t afford to take enough time off of her job at a local pharmacy to properly quarantine before taking Shahgodari to college. Shahgodari flew to Boston alone.

A friend in the area picked her up from the airport with supplies for her dorm that wouldn’t fit in the suitcases. She only had a few hours to move in with her friend’s help. They worked quickly, but so did the clock. It wasn’t long before she was left alone to finish unpacking and begin her mandatory quarantine.

“I would just make that the center of my day, when I could go to my COVID test, because I actually get to be outside for 15 minutes. I would walk really slowly to get my test, walk really slowly to come back, and just soak up as much of the outside as I could,” she said.

She spent four days alone in her dorm in a new city. Interim director of residence life, Amelia McConnell, said in a statement that students were required to quarantine until they received two negative results from COVID-19 tests performed by the university. Meals were delivered to the dorm room so Shahgodari wouldn’t leave the building. She washed her hair with body soap because she didn’t have shampoo and couldn’t leave to buy any. She wasn’t allowed outside.

To make matters worse, her roommate never moved in. Shahgodari is living in a suite designed for four people. It’s a large space, with a common room, private bathroom, and two bedrooms each meant to house two students. To keep distanced, Shahgodari was supposed to live in one room of the suite, and her roommate was supposed to live in the other.

But before they were set to move in, she says her roommate got sick. Shahgodari didn’t say what her roommate’s illness was, but it prevented the other student from moving in during the set time. Once she was better and able to move in, the roommate decided to stay home.

“I’m a really social person and I kind of get really upset when I’m by myself for too long,” said Shahgodari. She knew other people living in suites had roommates with them during the quarantine process so she felt lonely. It frustrated her to be by herself, but she made a daily routine to pass the time.

The Massachusetts Department of Mental Health created a web page devoted to dealing with isolation and loneliness during COVID-19 pandemic. They cited a 2014 study published in the Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research that found loneliness due to social isolation can worsen symptoms of mental illness. The Department of Mental Health suggests ways to cope with the loneliness that comes with a time of social isolation, including setting up virtual hang out sessions, reaching out to loved ones, and going on walks.

The outdoors has become an outlet for Shahgodari. She has taken up walking around the near-by Muddy River Reservation to give herself a change of scenery. But she still sometimes feels that loneliness.

“I definitely have my moments and I kind of am like ‘oh my god, I have no friends, this is the worst’ and then I kind of have to tell myself ‘you do have friends, everybody’s busy, it’s hard to hang out with people.’”

She’s been able to make friends with three other first-year students who live on her floor. Sometimes they’ll get dinner from the dining hall together, but that has changed as well.

Students either have to order online and pick the food up by appointment, or be served the normally self-serve buffet food by the staff, says Shahgodari. To spend dinner together, they take food outside to the quad and eat in distanced adirondack chairs. But with winter creeping in, eating meals together outdoors will likely become impossible, and this Floridian has recently bought her first winter coat.

Shahgodari’s mom is worried about her. She calls her daughter frequently.

“I’m the baby that also is going to college, and I happen to be going to college over 1000 miles away,” said Shahgodari. Her brother is 13 years older than her and never went to college. She said her mom was “terrified” for her to go but recognizes that it’s likely very tough for her mom to have her daughter so far away, especially during a pandemic.

Shahgodari has to move out November 24, just a week away. Her on-campus experience is cut short so that students will be fully moved out before Thanksgiving. “This decision was made to minimize potential COVID-19 exposure after the holidays where travel and family gatherings are common and as cases continue to rise here and around the country,” said McConnell in an emailed statement.

But Shahgodari wants to come back. Despite the loneliness, the distance from family, the restrictions, and the stinging COVID tests, she believes that physically being at Simmons allowed her to focus more.

“Online school is very hard for me as it is and I think the change of environment does help me a lot,” she said. She’s ready to reapply to live on campus for the next semester.

Click down below to listen to a day in the life of Zari Shahgodari.