By Simran P. Gupta

Staff Writer

Many would describe ballerinas—pre-professional, professional, or otherwise—to be tiny, pretty things. After all, it is the cookie-cutter default, right? Doesn’t every ballet dancer aspire to be described as such? Well, maybe not, and the world of ballet has never been that simple.

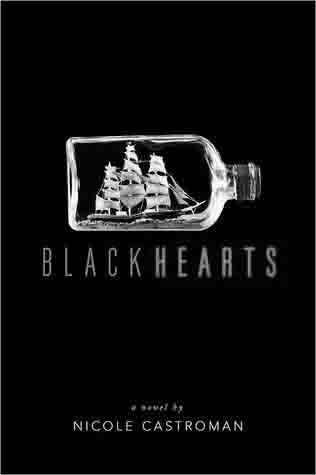

The brilliant young adult novel “Tiny Pretty Things” by Sona Charaipotra and Dhonielle Clayton dives into the pre-professional world of ballet, exposing the beautiful and the ugly.

One of my favorite aspects of the novel is how it tackled issues of diversity in ballet. It’s true that it’s a whitewashed performance art, and it has been for centuries. The fact that it’s taken us this long to recognize black talent in the form of Misty Copeland is incredibly problematic. Written by two women of color, “Tiny Pretty Things” presents a perspective on this issue that many other writers cannot translate into their work.

Another plus for Clayton and Charaipotra’s storytelling is the way they tackle issues of addiction, family life, and eating disorders, and the way the pre-professional environment only exacerbates such personal problems.

Our three protagonists deal with these issues in a very intersectional way, which made the book very real, human, and heartfelt. You’ll find yourself crying even with the supposed “mean girls” of the company.

“Tiny Pretty Things” follows three girls: Bette, June, and Gigi. Written in chapters of alternating viewpoints, we realize that even the most apparently one-dimensional character is complex and has many layers. Gigi, short for Giselle, hails all the way from California and is late in transferring to the American Ballet Conservatory. She has less money than most of the other dancers, is the only dancer of color at her level, and has spurred in many of her peers a vicious jealousy, causing them to try and root her out.

Her arrival and talent threatens previous golden girl and pre-professional favorite Bette, who exemplifies the ballet stereotype: thin, blond, white, and graceful.

It is with this character that the authors reveal their genius. Introduced as a ruthless, relatively static, somewhat bratty character already at the top, Bette’s downfall is witnessed by the reader. It is clear that she has gone through somewhat of a negative metamorphosis; by witnessing her downfall, we can identify with her problems and understand (though not excuse) the motivations behind her cruel pranks.

Memories involving starvation at the hands of parents, being locked in basements, and pressure to perform at the level of a ballet-superstar older sister are revealed through interactions with a drunkard mother; a cool, barely there sister; and the rest of the people in their high socioeconomic status.

The authors create a similar effect with June, but through a slightly different technique. She is introduced as already cold and closed off. We do not see her downfall, but we begin to see her as human through various interactions with her traditional and aloof Korean mother.

Cultural pressures are what motivate June’s competitive edge, as well as the threat of being pulled out of the company if she cannot land a spot in the professional American Ballet Company. Now and then, June longs for the comfort of a friend or boyfriend, but cannot allow herself to open up to her roommate and new competition, Gigi.

Through these three characters, Clayton and Charaipotra examine issues in the otherwise static world of ballet seamlessly. Through the character Will and June’s previous friend Sei-Jin, the issue of sexual orientation and gay visibility in dance is discussed.

Through Bette’s diet pills and June’s constant struggle with bulimia, the authors shed light on the normalization of eating disorders in the pre-professional ballet world. Gigi and June are vehicles for exploring issues of cultural identity and confronting racism in ballet, especially in the staunchly “ballet blanc” tradition of Russian ballet.

And yet we are reminded that these aspiring characters are ballerinas and are still only young adults. They struggle with friendships, families, and first loves. Bette struggles with reshaping her identity after her childhood love, Alec, breaks up with her for Gigi. Will struggles to reconcile his sexuality and romantic feelings for Alex while still trying to be his friend.

Somehow, with all this packed in, the book never loses the sense that the story is a thriller, fast approaching a dangerous climax. A terrible accident at the end causes the book to end with a kind of “whodunit” mystery conclusion, with several seeds planted by authors and hints about who the culprit may have been.

Without giving anything away, the last line of the book is spoken by June: “I realize that in ballet, no one is ever safe.” And with that chilling line, we are left to ponder the masterpiece that is this debut.

The icing on the cake is that the book, in the simplest sense, still conveys the passion any young dancer has for ballet as a form of expression, movement, and art. And that, I think, will strike a chord in every reader that picks up “Tiny Pretty Things.”